Death and the coffins

Many of the documents in the archives of St. Jørgen’s Hospital provide us with a small reminder of how death must have once been a constant presence in the hospital. No one could expect to be healed, and almost all who came to the hospital remained there for the rest of their lives. The patient registers, which mainly record when they arrived and when they died, bear clear witness to the fact that, for the vast majority, death was their only way out of the hospital.

Those who came to the hospital in the 18th century were often so ill that they died after a relatively short time, but even then, some patients lived for a long time. The residents did not necessarily die of leprosy, either. Many of them died from other common illnesses. This is a pattern we also see in the other leprosy hospitals.

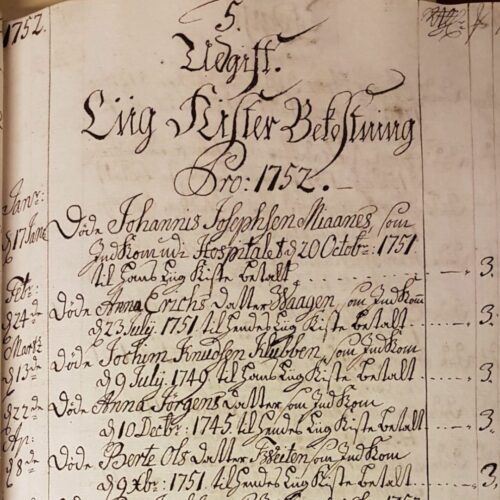

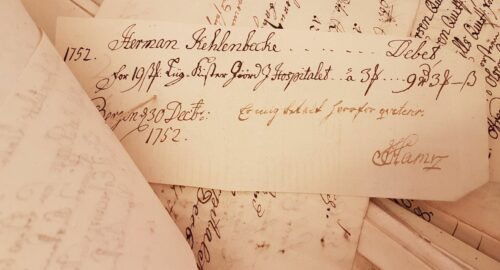

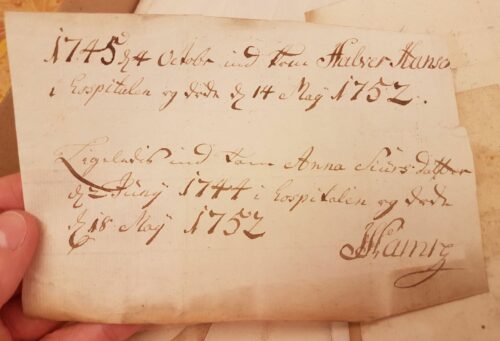

Death also left its mark in the hospitals accounting documents. In 1752, nineteen of the residents of St. Jørgen’s died and among the accounting documents we find a small pile of certificates confirming the deaths. The small notes tell us when each of them arrived at the hospital and when they died. The patients also appear in the accounts of expenses relating to the coffins, where they are listed one by one, and receipts show payments for the production of coffins. It was the hospital that had to pay for coffins for deceased residents, in the cheapest way possible.

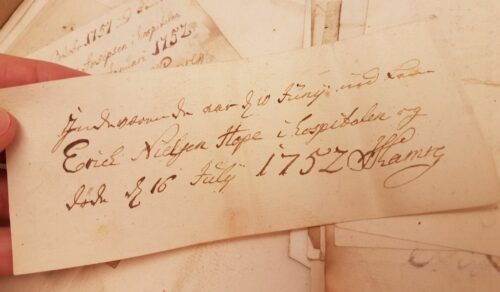

On average, one resident died about every three weeks that year, although some months had fewer or no deaths and some months more. Four patients died in May. One of them was Anna Siursdatter, who was the deceased who had been at the hospital the longest. When she died on 18 May 1752, she had been living at the hospital for almost eight years. Halver Hansen, who died four days earlier, had been at the hospital for seven years, since 1745. However, many residents died soon after being admitted. Erich Nielsen Hope arrived on 10 June 1752 and died just over a month later, on 16 July.

Photo: Ingfrid Bækken. Bergen City Archives.

Photo: Ingfrid Bækken. Bergen City Archives.

Photo: Ingfrid Bækken. Bergen City Archives.

Photo: Ingfrid Bækken. Bergen City Archives.