Isolation – at home or in hospital?

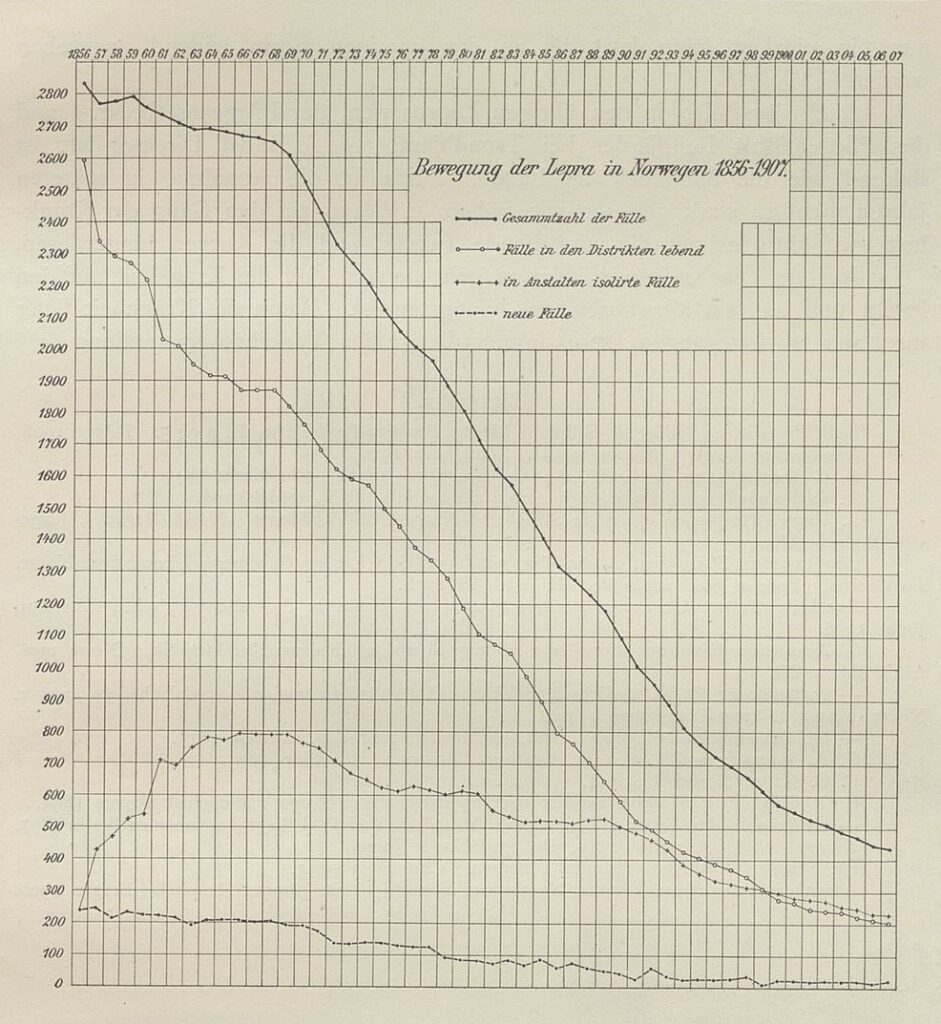

Even though Norway was seen as a role model when it came to isolation as a preventative measure, at no point were all of those registered as having leprosy admitted to hospitals or care institutions. There simply was not the capacity. From around 1860, the four state leprosy hospitals plus the old St. Jørgen’s Hospital only had capacity for about 800 patients. As cases of leprosy decreased towards the end of the 19th century, a number of the hospitals eventually closed.

In addition to the legislations from 1877 and 1885 allowing the use of force in special cases, there were other measures that could increase the number of people being admitted to hospital or care institutions. Economic considerations were an important factor. Once admitted to a state care institution, it was the state that covered the patient’s expenses, relieving families and local communities the burden of providing for and supporting them. As many of those who developed leprosy came from impoverished backgrounds, a fair number of them probably applied for a place when they could no longer contribute to their household and began feeling like a burden on their families. Over time, the growing focus on the infectious nature of the disease likely led to fear in local communities, increasing the pressure for those with leprosy to be hospitalised.

Many still chose to and were allowed to live at home. According to an overview in Hansen and Looft’s book ‘Leprosy in its Clinical and Pathological Aspects’ from 1895, it wasn’t until 1890 that more people registered with leprosy were staying in hospitals than living at home. Later overviews, which presumably had corrected figures, indicate that this occurred even later. The printed version of Hansen and Lie’s presentation at the International Leprosy Conference in Bergen in 1909 states that it wasn’t until around 1900 that more people with leprosy were staying in hospitals than living at home.

Lie describes in an annual report from 1930 that by the end of the year, there were 45 people staying in hospitals and 24 living at home. Most of those living outside institutions had mild symptoms, and the risk of transmission was assumed to be low, providing certain safety measures were followed. In 1936, 28 leprosy patients were staying in hospitals and 17 were living at home. All of those living at home were under the supervision of district medical officers. In 1957, when the position of Chief Medical Officer for Leprosy was discontinued, there were five residents remaining in hospital, all of them at Pleiestiftelsen. There were also two people who had previously had leprosy living at home.