Hospital staff

Pleiestiftelsen Hospital was a large institution with many staff and most of them lived on site, whether a doctor and superintendent living in their own residences, or the subordinate ‘servants’ who shared rooms in the main building. Some of the staff were educated and others were not, and there must have been a huge difference in status for the different positions. Nursing gradually evolved into a separate field, and nurses qualified by studying nursing.

It can’t have been the most attractive position for those starting at the hospital as a cleaning maid or young hired hand, with hard work and long days, as was the case for most servants. Some of the staff were from Bergen or the surrounding area, while others moved all the way from Sunnfjord or Sunnhordaland. One can only wonder why they applied to work at the hospital and whether they enjoyed it.

Photo: Atelier Knud Knudsen. The University of Bergen Library.

Staff in 1860 and 1891

A description from 1860 states that the hospital had 20 employees, all of whom lived and ate at the hospital. The most senior staff were the doctor, the chaplain, a schoolteacher who was also a cantor, a bookkeeper/accountant and a superintendent, who lived at the foundation and supervised ‘all the affairs of the hospital’. Of more subordinate positions, there were four ‘female ward orderlies’, four kitchen maids, a bathing girl, a bathing boy, a stoker, a porter and an ‘errand runner’. There was also a young man employed to assist the doctor with ‘nursing and preparing medicines’.

More than 30 years later, in the 1891 census, many of the positions remained the same, although some minor changes had been made to the subordinate ‘servants’. At that point, there were only three ward orderlies and kitchen maids, as well as two cleaning maids, although they then had a housekeeper, and a ‘senior ward orderly’ and matron. The bathing girl was now called a female bathing attendant, and the bathing boy was now also a cup setter. The stoker and porter were still there, but the errand runner had a new title and more duties. He was now referred to as a ‘messenger and horse hand’.

Photo: The University of Bergen Library.

Hospital staff in 1910

In the 1910 census, there were slightly fewer residents, but there were still three ward orderlies, two kitchen maids, two cleaning maids, and a male and female bathing attendant. All the ‘servants’ are described as living in six ‘servant rooms’ in the main building, and there was a shared bathroom for the servants and a bathroom for patients. The combined messenger and horse hand position was still going strong. The positions of housekeeper and matron remained, but the senior ward orderly was now a senior nursing officer.

There was also one completely new member of staff on the payroll – a laboratory technician. The titles give the sense that the hospital had evolved, with the care of patients becoming more professionalised, and scientific research now important. The doctor no longer had a young man to assist him.

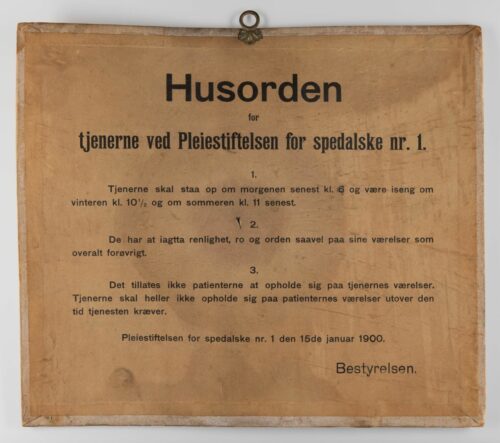

1. The servants shall rise at 6 a.m. at the latest and be in bed by 10.30 p.m. in winter and 11 p.m. at the latest in summer

2. They must observe cleanliness, peace and order in their rooms as well as elsewhere.

3. Patients are not allowed to visit the servants’ rooms. Nor should servants spend more time in the patients’ rooms than is necessary for the performance of their duties.

Pleiestiftelsen Hospital for Leprosy No. 1, 15 January 1900. The superintendent.’

Photo: Bergen City Museum.

The 1910 census provides a more detailed description of the doctor and superintendent who lived at the hospital with their families. The doctor and superintendent H. P. Lie lived in the residence towards the street with his wife and six children. His eldest daughter was listed as an upper secondary school pupil on the census form. Two maids and a nanny also lived at the residence. Superintendent Baastian O. Langlo lived in the other residence, along with a maid and his daughter who was a bank assistant. The census also lists a girl from Gudbrandsdalen living at the address. She was a music student and was perhaps a tenant or a friend of the family. There was also a small family in the main building who lived separately from the other staff. Gardener and farm hand Johannes Larsen lived with his wife and son who was a ‘runner boy’.

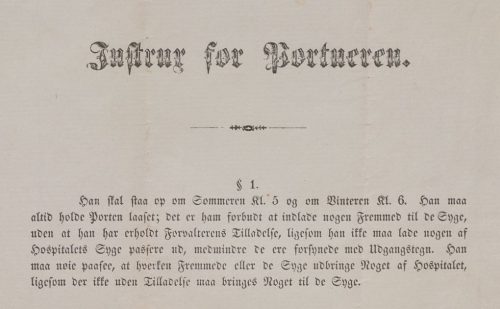

One of the residents, Jørgen Sørvær from Alstadhaug in Nordland, was listed in 1910 as a patient and stoker. It doesn’t seem uncommon for some of the patients to be assigned such permanent duties and titles. Nicolai Ordahl, who was employed as a cup setter at the hospital in 1898, recounted that one of the patients at the time was a porter and would answer the doorbell at the main entrance to the hospital.

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.

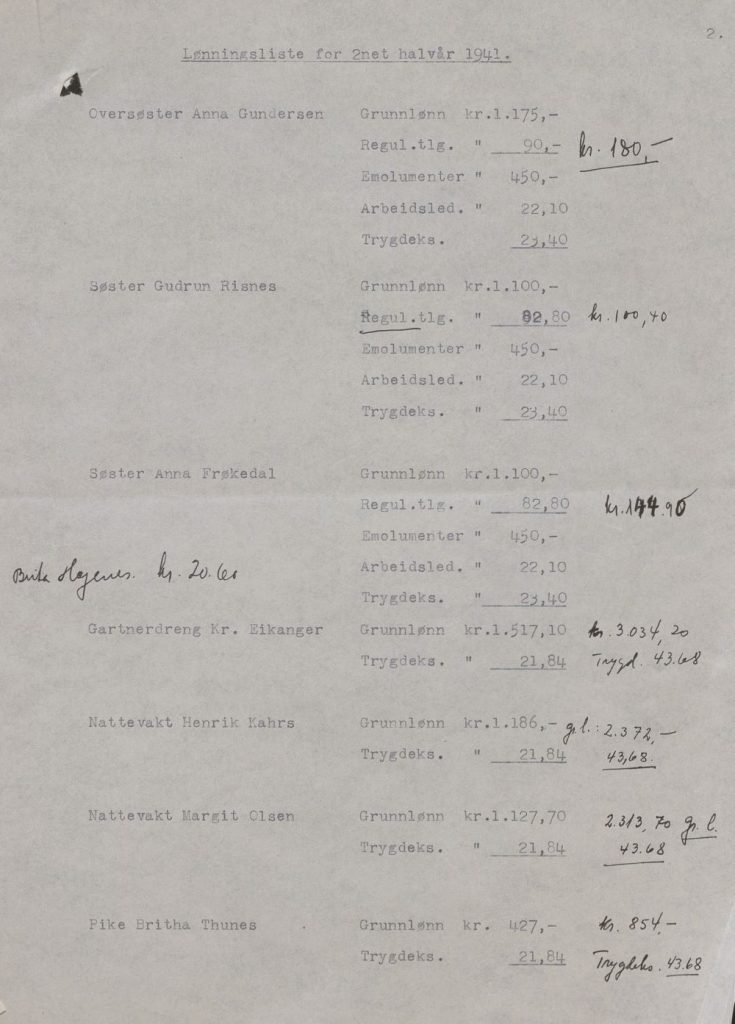

Five rooms in the main building were also rented to Lungegården Hospital, which treated people with tuberculosis. On the day of the census in 1910, 11 patients were registered here, as well as a deacon and eight nurses. The tuberculosis hospital took over the old Lungegaard Hospital on the neighbouring property in 1895, but due to a lack of space they rented some rooms in the south wing of Pleiestiftelsen Hospital. The nurses, who were all unmarried, lived there. The nurses probably cared for all the tuberculosis patients, regardless of whether they had rooms at Pleiestiftelsen or at Lungegården, and several of them may well have stayed at the hospital for practical reasons. The hospital had a cooperation with schools of nursing, such as Betanien, allowing students to work at the hospital as part of their education.

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.