Kari Nilsdatter Spidsøen

Kari was born on 17 July 1847 at Øvre Spissøy farm, which is now situated in Bømlo municipality. She was the eighth child of Nils and Brita, but two of her older siblings had already passed away when she was born. Kari’s parents owned the farm but were facing financial difficulties. In order to make ends meet, they had to divide the farm and sell half of it a few years before she was born.

Kari’s upbringing is not well-documented, but we can assume that being one of many children in a poor farming family on the west coast of Norway can’t have been easy. The family was also heavily impacted by leprosy. The father, stepfather, and three half-siblings of Kari’s mother had leprosy, and when Kari was four years old, two of her older siblings were also registered with the disease. By the time Kari was seven years old, she already had three younger siblings.

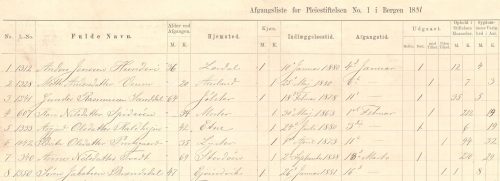

In 1856, a few years of extreme misfortune began for the family of eleven. The eldest son, Nils, died of leprosy at the age of 23, while still living at home. The following year, two of Kari’s sick siblings, Synneva Christine aged 22 and Øystein Johan aged 12, were sent to Pleiestiftelsen Hospital in Bergen. In 1858, the eldest sister, Brita, was also registered as having leprosy and was also sent to Pleiestiftelsen, while the older brother, Mikkel, moved away from the village. In just three years, Kari went from being the third youngest of nine children in the household to being the eldest of four. She was eleven years old.

Things didn’t improve for the family over the years. In 1859, the farm was sold at a forced auction, and the family became tenants on the property. Two of the siblings at Pleiestiftelsen, Synneva Christine and Øystein Johan, passed away in the summer of 1861. The youngest of them was only 15. The district medical officer in Finnås kept a close eye on Kari, as she had three siblings with leprosy, and in 1863, she herself was registered with the disease. At the age of 15, just after her confirmation, she left her family to live where two of her siblings had recently died, at Pleiestiftelsen in Bergen.

Kari’s adult sister Brita was still at Pleiestiftelsen, so the 16-year-old had at least one person she knew among the 300 patients. She lived in one of the seven-person rooms, and her days were filled with work and routines. There were four simple meals a day and fixed times to get up and go to bed.

In 1868, Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen became the new physician at the hospital. That year, Kari developed necrosis in her leg, and it was probably the new doctor who performed the procedure. Like many leprosy patients, she gradually experienced more health problems as the years went by. Her fingers became crooked and stopped functioning properly, she had open sores and scar tissue, and partial paralysis of her face.

When Kari was brought into Hansen’s office in 1879, she was 32 years old. She had spent half of her life at Pleiestiftelsen and had known Hansen for 11 years. Her sister Brita had been with her during all her years in Bergen, but had passed away just over a month earlier, and now Kari was alone.

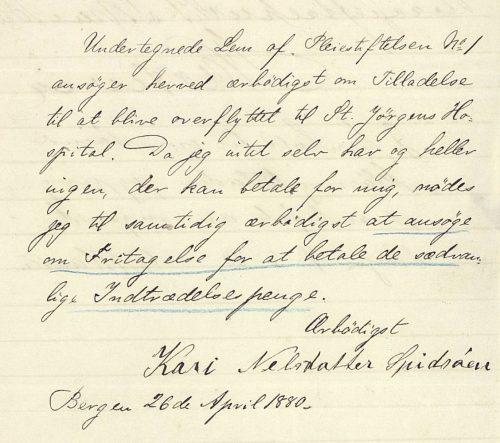

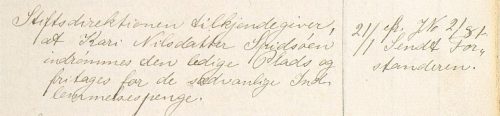

After the trial against Hansen, it may have been uncomfortable for her to continue living at Pleiestiftelsen, as Hansen remained closely associated with the hospital even though he was no longer the physician. She applied to be transferred to St. Jørgen’s and lived in one of the patient rooms in this building until her death in 1884. She was 36 years old and had been living in institutions since she was 16 years old.

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.

Bergen City Archives.

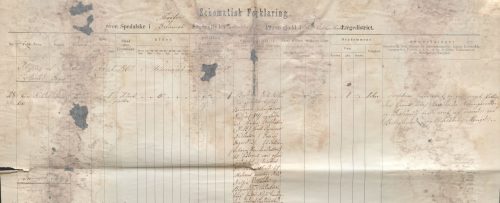

From one of the medical records at St. Jørgen’s Hospital. Bergen City Archives.

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.