Pleiestiftelsen’s main building

When Pleiestiftelsen Hospital was completed in 1857, it was Norway’s largest wooden building. It comprised over 7,000 square metres and could accommodate 280 patients.

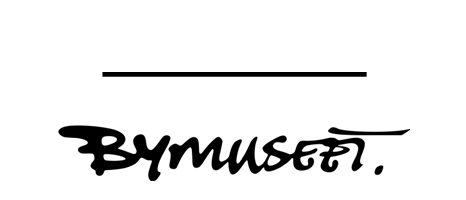

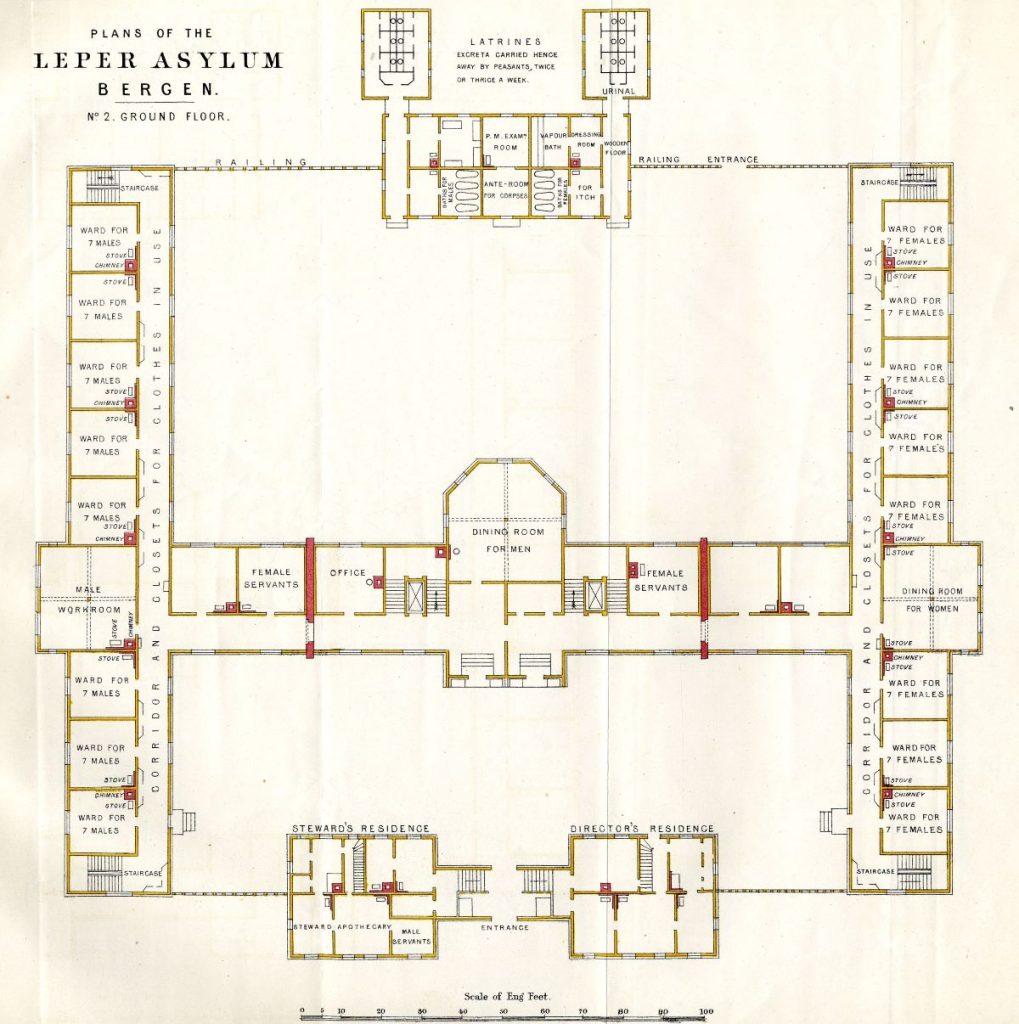

The main building is on two floors, with a central wing and two perpendicular side wings. There were sixteen patient rooms in each side wing, eight on each floor. Each room was about 33 square metres and could accommodate seven residents. There were also four patient rooms at each end of the middle wing, bringing the total to forty patient rooms. In each of the side wings, a bright corridor with windows on one side provided access to the patient rooms on the other side. There were also four large workrooms, two in each wing.

Men and women stayed in their own separate side wing. When Pleiestiftelsen was built, the theory that leprosy was a hereditary disease still prevailed, so it was considered vital to keep men and women apart. However, the head physician recounts that they did have some contact: ‘The building is divided equally into two halves, one of which is reserved for men, the other for women, without the isolation being so absolute that no kind of interchange can take place.’

There were two double entrance doors in the central building towards the courtyard facing the street, and men and women each had their own entrance. There were also stairs from the central wing up to the first floor to what was originally referred to as a ‘consecrated prayer room’, and later as a chapel. There was a large dining room on the ground floor below the chapel. Women and men later ate in separate dining rooms.

Photo: The Regional State Archives of Bergen.

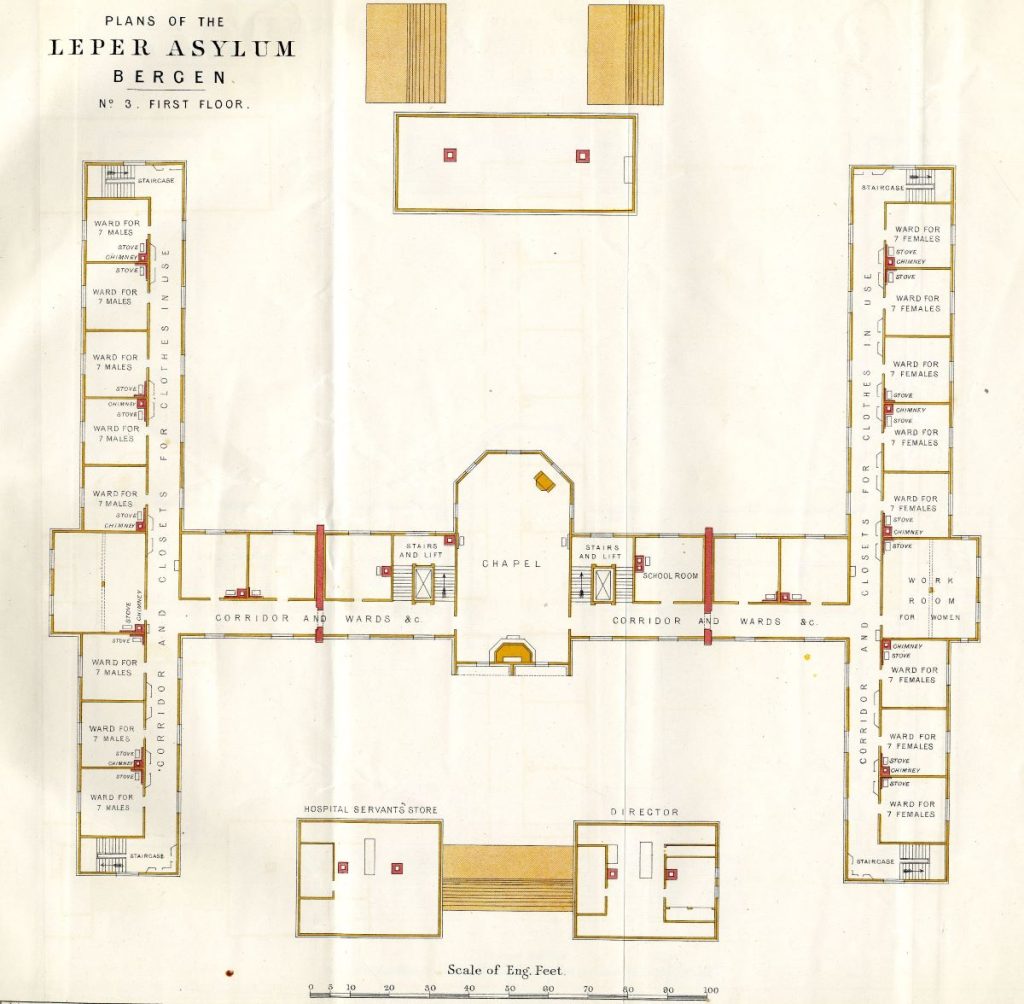

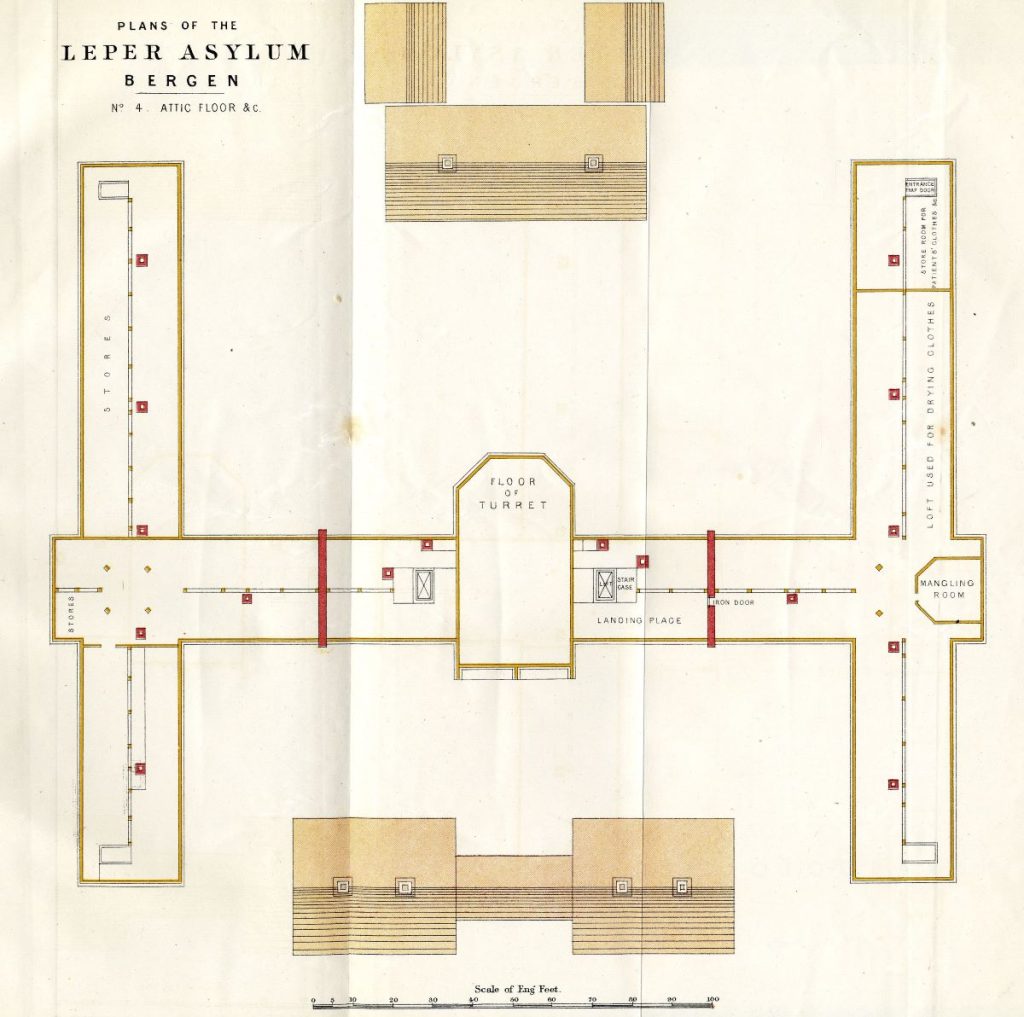

Besides that, there were two rooms in the central building for ‘female service staff’, a classroom, and an office for the superintendent. The basement housed a kitchen and laundry, as well as a storage area for food and firewood. The kitchen had a steam boiler, which also provided steam for the laundry and the bathing facilities at the rear. The steam was led to these facilities via pipes under the rear courtyard.

The entire building was made of wood, despite the dramatic fire at Lungegaard Hospital in 1853. Nevertheless, they must have been concerned about the risk of fire, because two brick fire gables were built on each side of the central building, where an iron door could close off the passage. According to the regulations, smoking was strictly prohibited inside the buildings, ‘where the greatest care when handling fire is of the utmost imperative’.

The institution was regarded as exemplary and illustrations of the buildings were disseminated in, for example, Henry Vandyke Carter’s ‘Report on Leprosy and Leper-asylums in Norway; with references to India’ from 1874.