St. Jørgen’s Hospital

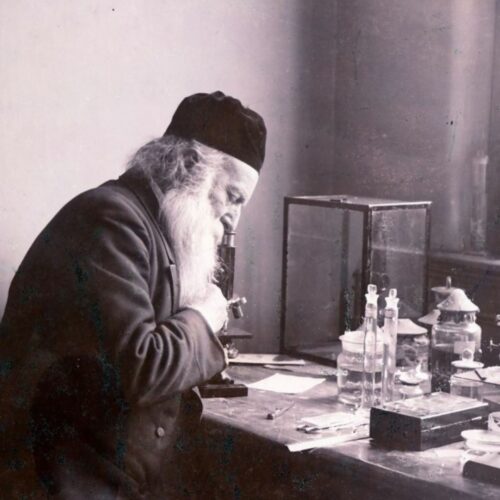

Photo: Regin Hjertholm.

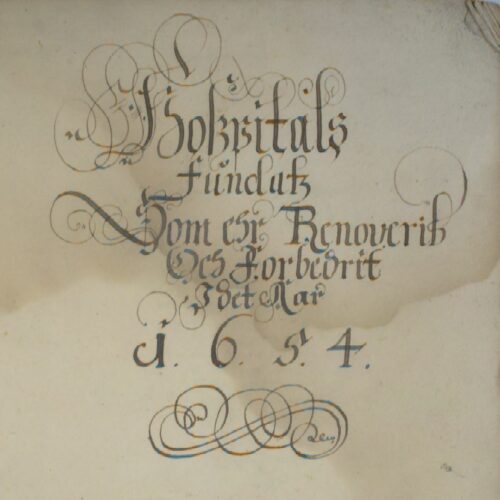

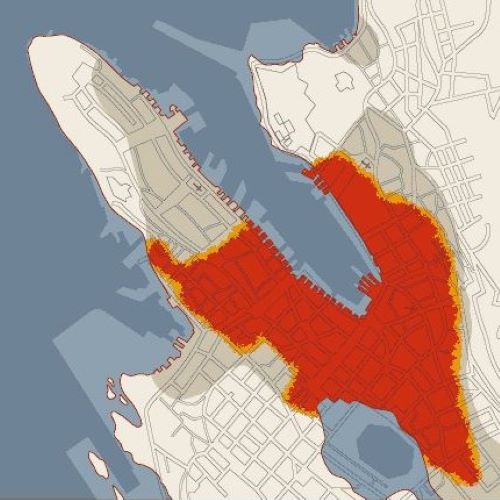

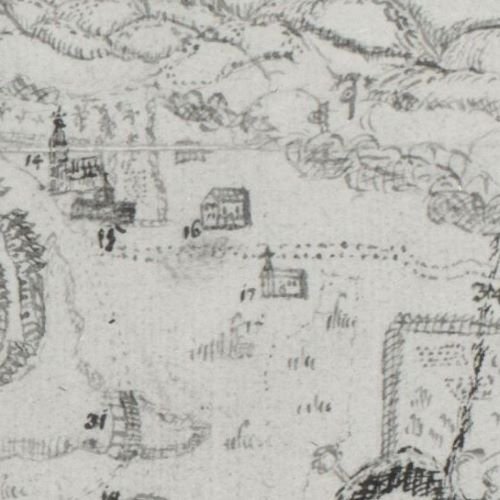

St. Jørgen’s Hospital has been part of the cityscape since the early 15th century. The earliest mention of the hospital is in a will from 1411, where it is referred to as ‘the hospital by Nonneseter’, and five years later it is described as ‘the new hospital’. The name St. Jørgen’s was first used in 1438. The hospital was situated on the grounds of Nonneseter monastery and may have been established by the monastery. There are, however, no sources that tell us anything about how or by whom the hospital was established. Originally, the facility was situated outside the city centre, along the main road south out of the city. After a number of city fires, nothing remains of the medieval buildings, but the hospital has been situated on the same site for over 600 years.

There have always been people with leprosy living at St. Jørgen’s Hospital, but at certain times the hospital was defined as a general hospital that also admitted people with other illnesses, as well as healthy people, often elderly people and those in need of care. It would not be considered a hospital by modern standards but rather primarily a place of residence for the ill.

The number of residents has varied considerably. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the hospital typically had between 60 and 150 residents. In the early 19th century, when leprosy was on the rise and there were few institutions to deal with it, the hospital operated at or beyond capacity. In the 1830s and 1840s, there were up to 170 people living at the hospital. At that point, it stopped admitting people with other illnesses or healthy people in need of care. By the mid-18th century, four leprosy hospitals had been established in Norway, while the number of new leprosy cases was falling. The number of residents at St. Jørgen’s was also decreasing. The last residents moved into the hospital in 1896. Nevertheless, the hospital remained in operation until 1946. During its final years, there were only two elderly women living there. They both died in quick succession in 1946 at the ages of 78 and 82 years old. They had both lived at St. Jørgen’s for more than 50 years.

St. Jørgen’s Hospital is a unique piece of cultural heritage. Today, the compound consists of ten various sized buildings, most of which date from the 18th century. The hospital was run by a foundation and the compound is still owned by the very same foundation. In 1970, the Leprosy Museum was established, and it has since been possible to visit parts of the main building and the church. Bergen City Museum now runs the Leprosy Museum St. Jørgen’s Hospital, which is open during the summer season.

St. Jørgen’s Hospital compound

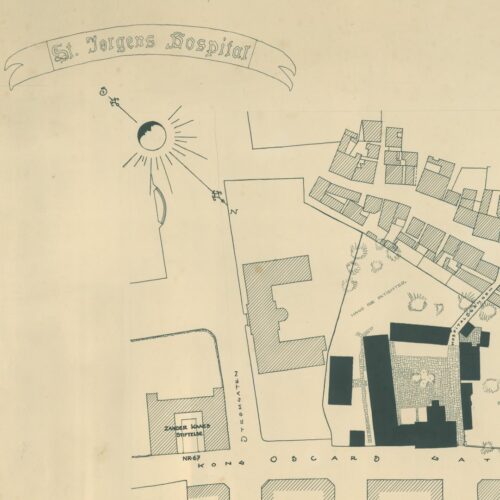

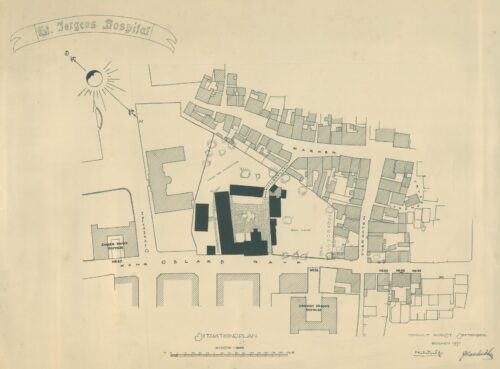

Survey drawing by Lindstrøm and Tvedt 1921. The archive of the National Association of Norwegian Architects, ArkiVest.

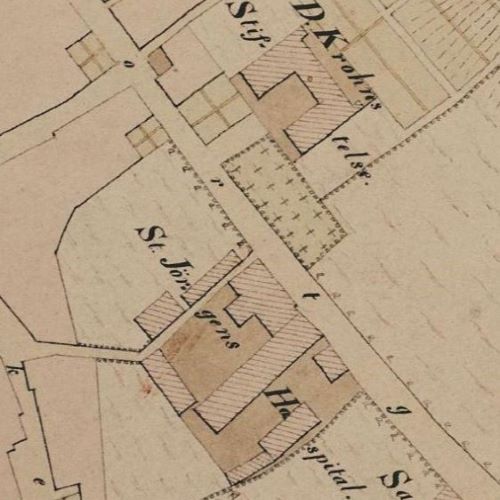

St. Jørgen’s is a unique 18th century hospital in the district of Marken in Bergen. Today, the hospital compound consists of ten various sized buildings, most of which were rebuilt after the city fire of 1702. The fire left the hospital and large parts of Bergen in ashes. The oldest of these buildings is the church dating from 1707.

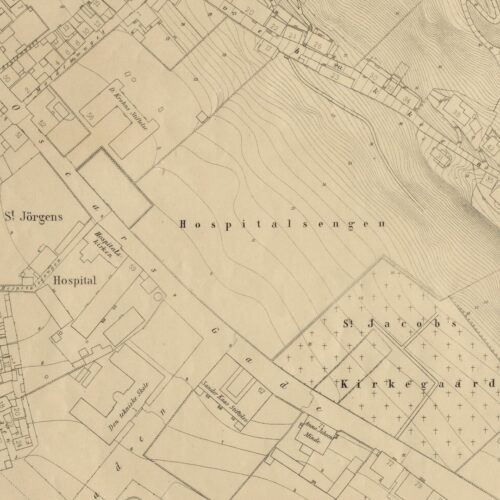

The church, the main building for residents, a ’healthy ward’, a parsonage, a farm building and other outbuildings all surround a paved courtyard. The hospital can be accessed from both Kong Oscars gate and from Marken. There is a garden behind the farm building where a herb garden was established in 1993. The hospital originally owned two gardens and sizeable pastures around the buildings and on the other side of Kong Oscars gate, an area formerly known as Hospitalsengen. St. Jørgen’s had its own cemetery on parts of Hospitalsengen.

The facades facing the courtyard are now painted green. The church and the facade of the main building facing Kong Oscars gate are painted white, while the rear sides of the other buildings are painted ochre yellow. If you had visited the hospital in the mid-18th century, the church would have been painted red, while the main building built in 1754, was painted white. Earlier in the 18th century, both buildings would have been tarred, and the church was first given wooden cladding when it was painted red in 1749. There were also fewer buildings around the courtyard in the 18th century.

The whole building compound was given listed status in 1927. Its cultural heritage value is particularly linked to its harmonious architectural design and to its continuous use as a hospital for more than 600 years.

The main building

The main building was taken into use in 1754 and was at that time described as ‘one of the very biggest and most impressive in the town’. It primarily contained bedchambers at both ends of the building, with two kitchens in the centre, passageways and small storage areas in the loft.

The small ward

The small ward had 16 bedchambers and was originally reserved for people designated ‘healthy residents’, i.e. people without leprosy who had paid to stay at St. Jørgen’s for the rest of their lives. It later became the place where women with leprosy would reside, and it was there that the last remaining residents lived.

St. Jørgen’s cemetery

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the hospital had its own cemetery on the other side of Kong Oscars gate. Later on, residents were buried at the large new cemeteries in the city: Møllendal and Solheim. Some were also buried in the places from where they came, at the request of their families.

The row of outhouses

Between the parsonage and the gateway towards Kong Oscars gate, there is an elongated building comprising five storerooms. At the end of the 19th century, it housed an office for the superintendent, a carpentry workshop, a storehouse, a mortuary and another storehouse towards the gateway to the hospital.

The gardens

The hospital originally owned two gardens. The garden on the north side of the hospital was sold to the municipality, while St. Jørgen’s still owns the garden behind the farm building. A herb garden was established there in 1993, with plants that have traditionally been used as food or medicine.

Everyday life

It’s easy to imagine that the days at the hospital must have felt long and monotonous. For many residents, the days were no doubt filled with pain and longing, and being separated from their families must often have caused distress. Other residents probably felt the hospital was the best place for them after they became ill. Many of those living at St. Jørgen’s had more contact with the outside world than one might imagine, with visitors, trips home for a few weeks at a time, selling goods at the market and interactions with others in the church. Not least, the residents must have had a sense of community among themselves.

The hospital was primarily a home, and everyday life there was very different from what we might associate with a hospital today. For residents with a reasonable functional ability and state of health, the days were filled with different duties. For long periods of time, residents who were able were expected to prepare their own meals. All residents were also expected to work to the best of their abilities. Some engaged in farm work and others in handicrafts, making various goods for sale.

Apart from a few isolated medical trials in the first half of the 19th century, there was little medical activity at St. Jørgen’s, and thus little hope of recovery. On the plus side, the residents had a considerable degree of freedom and were largely able to decide how they spent their days. That was probably one of the reasons why many of those admitted to Pleiestiftelsen Hospital applied for transfer to St. Jørgen’s, despite the fact the buildings were old and residents had to work if they were able. Although conditions at the hospital may now seem very basic and the bedchambers terribly small, it was probably what those moving to the hospital in the 18th and 19th centuries expected.

Most of those who moved into St. Jørgen’s stayed there for the rest of their lives. Some residents who had already been ill for a long time when they arrived would only live there for a few months, while others lived there for decades. They must have become very accustomed to the hospital and its routines, and watching other residents come and go. We do not know how many people have lived at St. Jørgen’s through the ages. What is certain is that the health of the residents varied widely, as did how they spent their days. As a rule, the disease was constantly advancing, although for those afflicted, some periods were better than others.

The residents and the city

It is a common misconception that people with leprosy have always been isolated from wider society. In the 18th and 19th centuries the residents of St. Jørgen’s lived relatively freely and were able to leave the hospital and walk the city’s streets. Until 1891, they were even allowed to sell their goods at the marketplace Torget.

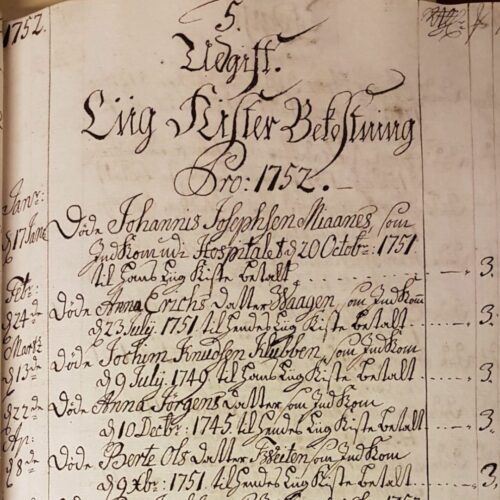

Death and the coffins

For the residents of St. Jørgen’s, death must have been a constant presence in the hospital. Many residents moved into the hospital shortly before they died, although a number of residents lived at St. Jørgen’s for a long time. The hospital had to pay for coffins for deceased residents, and did so in the cheapest way possible.

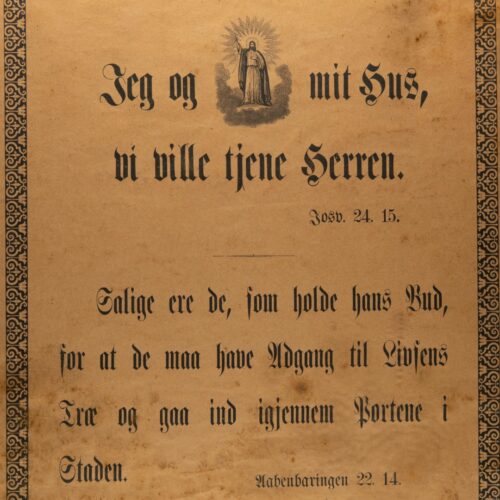

The residents and the church

The church and a religious way of life were an important part of the residents’ everyday life. Those who were able attended church services two days a week. The hospital had a chaplain long before it had a doctor, and the chaplain would have been the patients’ most important helper and spiritual advisor.

The conflict over the shoes

In the 1740s, the residents of St. Jørgen’s produced so many shoes that a conflict arose with the shoemaker’s guild in Bergen. In 1750, they were granted permission by the king to sell clogs to poor people and farmers, since the food allowance they were given was insufficient.

Library circulation ledger

There was a small library for the residents at St. Jørgen’s, and a circulation ledger spanning a ten-year period from 1843 has been preserved. In 1845, the library had 65 volumes, most of which were religious literature. It appears that many residents and the hospital chaplain borrowed books.

Contemporary accounts

There are numerous written accounts from the hospital, most of which date from the 19th century. The descriptions and evaluations made by doctors, clergymen, residents and visitors to the hospital provide varied insight into what life must have been like at the hospital. Below is a small selection of the contemporary descriptions.

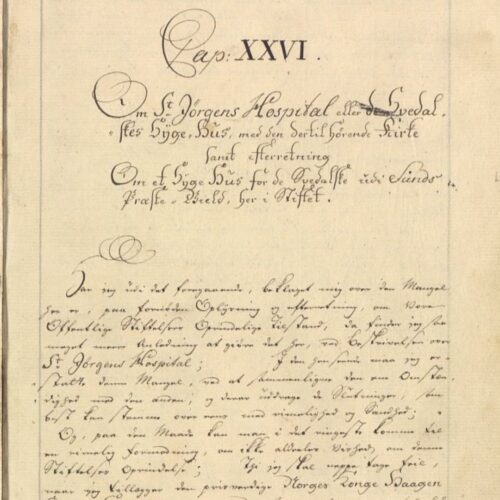

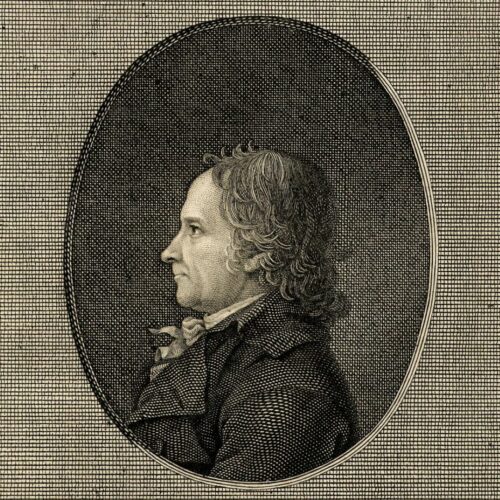

Professor Fabricius 1778

When the Danish natural historian and entomologist Johan Christian Fabricius visited St. Jørgen’s Hospital, there were 88 residents. He believed that the disease was caused by poor people’s way of life, not least their diet, and he was critical of the afflicted being seen as incurable.

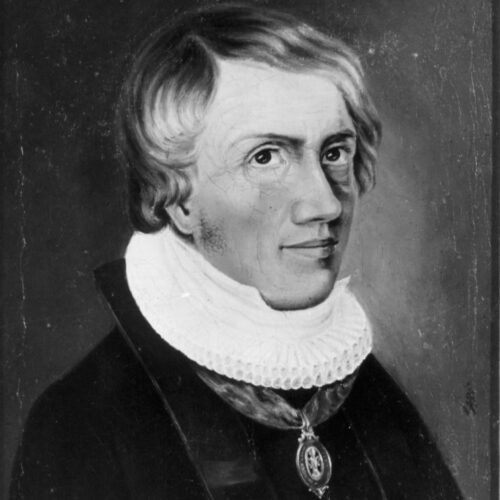

Chaplain Welhaven 1816

Welhaven was a chaplain at St. Jørgen’s for more than 20 years and cared greatly for the residents. His report can be considered the first scientific work on the disease at the hospital. It also included 32 unique drawings of residents, accompanied by their name, age and place of origin.

Peder Olsen Fedie 1835

Peder Olsen Feidie from Leikanger in Sogn lived at St. Jørgen’s Hospital for 17 years. The lament is one of four songs that he wrote and had printed by the printer Chr. Dahl in Bergen. The song is a rare eyewitness account of conditions at the hospital during the 1830s, from the perspective of one of the residents.

Danielssen 1841

D. C. Danielssen wrote an account of the hospital to the ministry two years after commencing his scientific research there. He was very critical of how the hospital was equipped and run, describing, among other things, the small, confined bedchambers, and patients being allowed to eat whatever they wanted and go out into the city whenever they pleased, except at night.

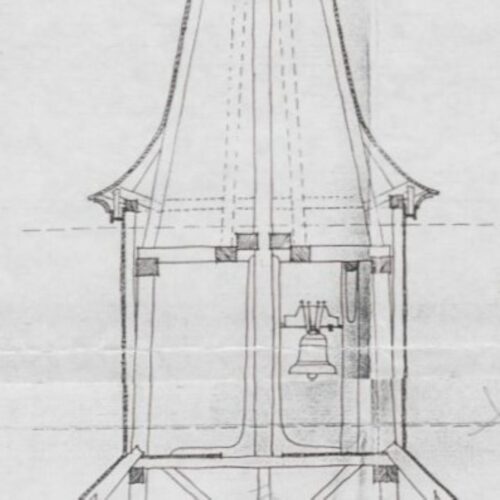

Lindstrøm & Tvedt 1921

The architects Lindstrøm and Tvedt conducted a survey of St. Jørgen’s that included a number of drawings of most of the buildings and a brief description of the complex. The survey clearly expresses the contemporary ideal of antiquarian buildings – anything considered an alteration or later addition are given little value.